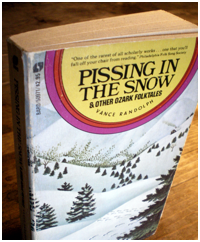

Pissing in the Snow by Vance Randolph was originally published by the University of Illinois Press in 1976, and reissued as a rack-sized mass-market paperback by Bard in 1977. In the late seventies, it was a best seller. The edition I have has a roller-rink-style ring of concentric circles around the title on a yellow background. It shows sparsely forested slopes with tracks in the snow. You can buy a copy from Amazon for a penny.

Pissing in the Snow by Vance Randolph was originally published by the University of Illinois Press in 1976, and reissued as a rack-sized mass-market paperback by Bard in 1977. In the late seventies, it was a best seller. The edition I have has a roller-rink-style ring of concentric circles around the title on a yellow background. It shows sparsely forested slopes with tracks in the snow. You can buy a copy from Amazon for a penny.

Vance Randolph was writer turned folklorist who moved to the Ozarks in 1920 and remained there until his death in 1980. He collected folk songs and folk tales and began publishing them in with university presses in the mid-1940s. Among the tales he collected, there were dozens he couldn’t publish. These folk stories contained “unprintable” words and the standard of the time was to either use a Latinized version or blank them out. Randolph wasn’t a fan of either method and kept the stories separate from the other stories.

As dirty stories, they depend on a kind of propriety that is fussy by today’s standards. Even the word propriety is a relic. Even so, the stock figure of the banker, church-going farmer, and farmer’s daughter remains as familiar as the woodcutter and princess. They are composed of units of meaning and these units appear repeatedly in the different stories. Typically the stories turn on a role reversal or a revelation of hidden information.

The title story is about two farmers. One farmer’s son “had been a-sparking” the other farmer’s daughter. One morning one farmer says to the other farmer, “I don’t want your boy setting foot on my place again.”

“Why what’s he done?”

“He pissed in the snow. Right in front of my house.”

“There ain’t no harm in that.”

“No harm! He pissed so he spelled Lucy’s name, right there in the snow.”

“He shouldn’t have done that. But, I don’t see nothing terrible in that.”

“I do! There were two sets of tracks. And besides, don’t you think I know my own daughter’s handwriting?”

Randolph follows each story with notes about the collection and variants based on different structures of story units. In reading these stories, I became aware that the stories were composed of words, but they were also composed of story units that followed a logic and that a certain order in the story units made the stories agree. In this way the order of the story units were like the order of words in a sentence, where a certain order is required, but other elements of the sentence can fall in a variety of orders; some of these orders are more agreeable than others. The Ozark tales as dirty and as oral stories sit at the margin between familiar forms such as dirty jokes and the kind of popular stories, such as ghost stories, that retain their oral roots.

Both my father and mother grew up in households before TV, and a common activity when they were little was to tell each other stories. My father is still angry about the arrival of the TV in his house because he recalls the evenings when everyone would sit around and tell these stories. They would retell stories they had read, things that happened, and stories they had heard. The stories came in two separate parts. There was the story recipe, which was essentially the collection of “story parts” and their order. And then there was the telling the story, that is the words used, the names used, and various tactics of execution such as delay, repetition, making voices and faces and so on. When the TV arrived, my father says they stopped telling stories and just sat in front of the screen. My parents tried to recreate this environment in their house in the mid-1970s. They didn’t open an operating TV. But by the late 1970s my mother became concerned about our “cultural literacy,” and they abandoned their exhausting project. We immediately started to watch Three’s Company.

A story is not necessarily how it is said, but is a portable structure that can survives transport, not just into another language, where diction and syntax are unlikely to survive, but into other media. In reading Vance Randolph’s collection of Ozark folktales, even more so than reading the Brothers Grimm, I understand how to use Roland Barthes’ idea in his great essay, “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” Narrative, Barthes writes, is “able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all of these substances.” Pissing in the Snow provides an essential great source of, for some, the basic narrative units of the American tale.

Rediscovered Reading is a regular series in which Matt Briggs reviews overlooked collections of short fiction. Matt is the author of Shoot the Buffalo and other books. He blogs at mattbriggs.wordpress.com.

One Reply

[…] | Tags: folklore, Review, Stories, storytelling | Leave a Comment nothing terrible in thatMy latest review for “Rediscovered Reading” at Fictionaught’s Blog has been posted. Pissing in the […]

Leave a Comment

trackback address